Intelligence Update

DCIM vulnerabilities escalate threat of cyberattacks

Cyberattacks exploiting data center infrastructure management (DCIM) software vulnerabilities could be more likely than many operators realize. Reports of common vulnerabilities and exposures (CVE) of well-known DCIM products are increasing, while ransomware incidents on critical data center infrastructure surge (see Ransomware incidents on OT equipment surge).

DCIM software is an attractive target for cybercriminals seeking to disrupt data center operations or use facility networks as entry points to infiltrate corporate systems. DCIM sits in the “grey space” between IT and facilities, where there can be unclear lines of responsibility for tasks, including cybersecurity of operational software.

Some enterprises and operators may run outdated or unsupported legacy DCIM software. Others may have modern DCIM software but have failed to implement the latest security patches or product versions. Many connect DCIM software to legacy operational IT and OT systems. These factors make DCIM software vulnerable to cyber exploits, particularly those related to user account compromises, unauthorized access and data manipulation.

DCIM software and its databases are likely to receive, share and store critical equipment data, related to IT infrastructure assets, such as servers, cabinets and racks, as well as their connected networks and power devices. This may include:

- IT and OT equipment identifiers. For example, original equipment manufacturer (OEM) device IDs, models, firmware, patches, support, warranty and life cycle information.

- Power connections, ports and line diagrams. These show the power delivery train to specific IT infrastructure.

- Telemetry data from equipment sensors. This data provides operational performance, efficiency, and resiliency information.

- Sensitive customer and operator data. This data can also be targeted by cyber criminals.

Few suppliers disclose vulnerabilities

The CVE program tracks known information security vulnerabilities and exposures in publicly released software. Such vulnerabilities are typically discovered by security researchers or software vendors and assigned a number by one of several CVE Numbering Authorities (CNAs) once the report is verified. Uptime Intelligence’s research has found that few DCIM vendors actively issue CVE notices, such as to the US’ National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) and the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA).

A recent Uptime Intelligence report assessed 20 DCIM software vendors against their product capabilities and their security credentials (see Data center management software: the evolving role of DCIM). However, over the past two years, only three DCIM software products have CVEs on these databases for enterprises and operators to review. It is unlikely that other DCIM vendors have not discovered vulnerabilities in their software during this period.

While CVE reporting remains voluntary in most jurisdictions, this is slowly changing. The Cyber Resilience Act (CRA), which came into effect in Europe at the end of 2024, will require DCIM suppliers, among other software and hardware providers, to report actively exploited vulnerabilities. However, the mandate does not go into effect until September 2026, and no equivalent exists in the US (see European cybersecurity regulation and its impact on digital infrastructures).

CVEs are increasing

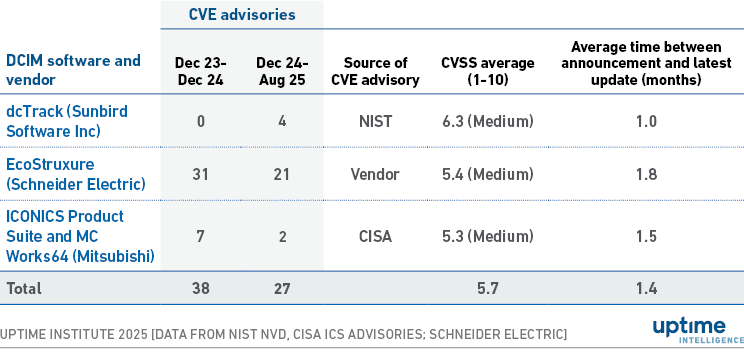

Uptime discovered 27 CVEs issued on three DCIM software products between December 2024 and August 2025. This figure represents 71% of the total DCIM CVEs published during the previous 12-month period (38 CVEs) — indicating a significant year-on-year increase (see Table 1 below).

Table 1 columns include the DCIM product affected, the number of CVE advisories in both periods, and their average CVSS (Common Vulnerability Scoring System) rating from 1 to 10 (low to high severity). CVSS ratings are based on several criteria, including the attack vector, complexity, privileges required, user interaction, scope and impact.

The table also includes the average time between the initial advisory notice and the latest published update, indicating the speed of response to the CVE advisory. All three vendors have issued responses within two months. These responses often include a new version of the software, a patch, or a “hot fix” release (an update released outside the normal update schedule). In some cases, however, suppliers provide contingency advice rather than issue fixes, particularly for older versions (see Table 2). Patches for older software versions can take years, while some older versions are no longer fixed to encourage version upgrades.

Table1 Publicly available DCIM CVEs and average CVSS ratings (2025 versus 2024)

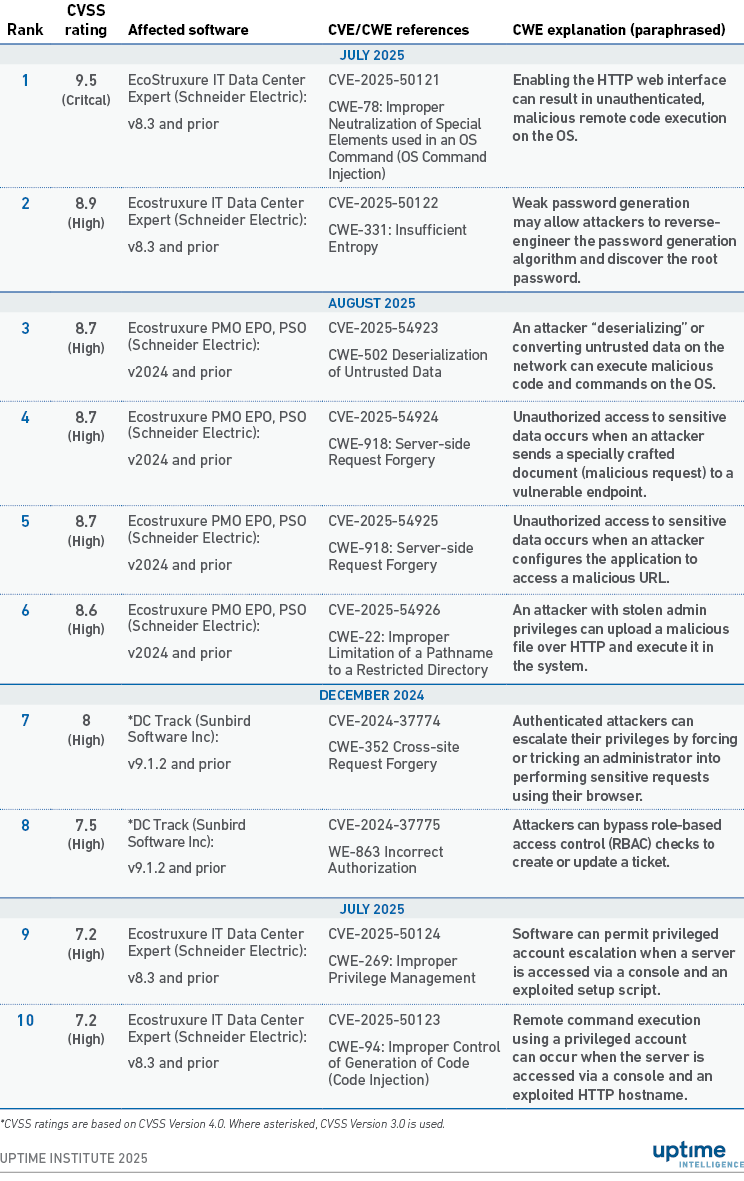

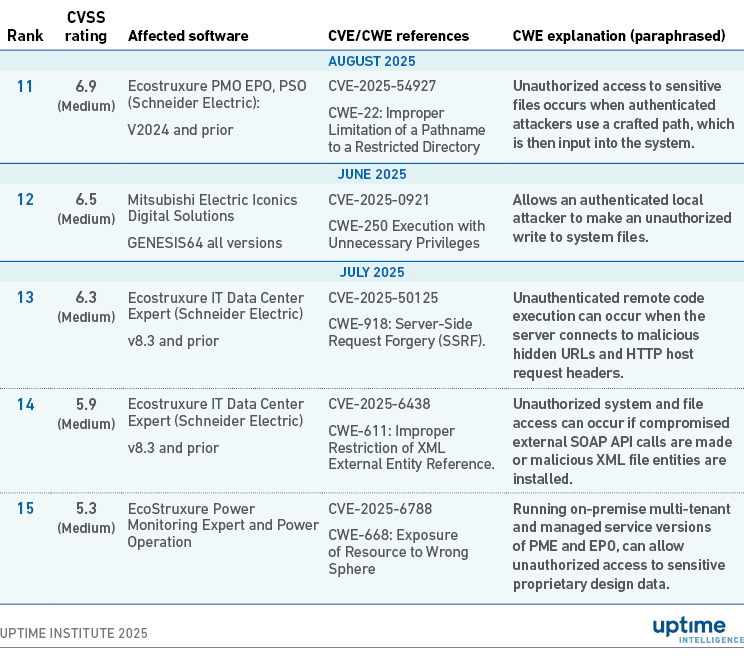

Table 2 lists 10 of the most severe DCIM CVEs identified in Table 1, based on their CVSS rating. The table explains their common weaknesses exposed (CWEs) and whether fixes or advisories exist. (The Appendix lists the following five most severe CVEs, ranked 11 to 15).

Table 2 Ten most severe DCIM CVEs identified between 2024 and 2025

Unauthorized access is key risk factor

The CVEs listed in Table 2 indicate that DCIM software products often share common weaknesses in authentication, verification and data protection. These factors could make DCIM software vulnerable to unauthorized access, account infiltration and data manipulation.

An unauthorized access attack involves an attacker gaining legitimate access to intercept, corrupt or steal data. They may issue fake requests to trick users into installing corrupt scripts, malicious code or malware. By using legitimate accounts (e.g., administrator), the attacker can often execute their attack while remaining undetected.

How could this happen? The following three scenarios outline how attackers might exploit specific DCIM vulnerabilities:

- Exploiting weak authentication to infiltrate legitimate user accounts.

- CWE-331: Insufficient Entropy. Weak passwords and ineffective password generators make it easy for attackers to steal legitimate user credentials.

- Exploiting weak verification to assume high-level administrative privileges.

- CWE-269: Improper Privilege Management. Using default settings and open permissions allows attackers to escalate their user privileges.

- CWE-250: Execution with Unnecessary Privileges. Escalated privileges can then allow attackers to compromise DCIM information, such as by adding or replacing trusted file directory data.

- CWE-668: Exposure of Resource to Wrong Sphere. Failing to verify other “spheres” of users in a multi-tenant environment can give unauthorized users access to sensitive information. Attackers in the system can also exploit this flaw for lateral movement.

- Exploiting the usage of insecure HTTP web browsers.

- CWE-352 Cross-site Request Forgery (CSRF): Authenticated users may receive a fake request requesting them to click on an external website or HTML links, which can inadvertently execute malicious commands on the system.

- CWE-78: Improper Neutralization of Special Elements used in an OS Command (OS Command Injection). Lack of verification on user input commands can result in the inadvertent copying and execution of malicious scripts from external web sources into the DCIM operating system.

Building a defense

The first line of defense is to patch the DCIM software to address the identified CVEs. Where possible, automated patching ensures that the latest software versions are routinely implemented.

In addition, the following steps might significantly enhance the security of existing DCIM systems:

- Utilize single sign-on (SSO) and multi-factor authentication (MFA) to add extra layers of security for authentication and verification. Zero standing privileges ensures that system access is only available when needed.

- Utilize real-time application and network monitoring to identify and quarantine malicious scripts, and alert users. Context-aware security information and event management software may help to identify anomalies in user behavior.

Operators looking to improve their cybersecurity posture will also:

- Encrypt all data in transit and at rest.

- Encrypt all login information and passwords on systems.

- Use encrypted browsers and up-to-date VPNs for off-site access to facility networks.

- Eliminate the use of inherently insecure legacy IT systems, such as HTTP web browsers and unencrypted remote web access tools.

The Uptime Intelligence View

Operators should not inherently trust DCIM users or user inputs – regardless of whether they are authenticated and verified. Suppliers have demonstrated a lack of consistency in their vulnerability recording, while patches and updates often fail to provide the immediacy required for real-time protection. Nonetheless, some suppliers are more transparent than others. Enterprises should favor vendors who disclose CVEs and are proactive in fixing any vulnerabilities.

DCIM software has security weaknesses; therefore, it is the operator’s responsibility to remain constantly vigilant and proactive in mitigating potential threats.

(A future report will examine CVEs related to operational technology and industrial control software.)

Appendix: Additional DCIM CVEs by CVSS severity

Other related reports published and webinars by Uptime Institute include:Data center management software: the evolving role of DCIM European cybersecurity regulation and its impact on digital infrastructuresRansomware incidents on OT equipment surge